The Authoritarian Shadows and Amusing Ourselves to Death – Reflecting on Malaysia’s Media Freedom 20 Years After the Malicious Acquisition of Nanyang Press

By Oung Kang Wei (Event organising committee)

Translate By Leong Jie Yu

Are there any lessons left from the malicious acquisition of Nanyang Press 20 years ago? We could not help but ask. At this day and age where everyone can be a self-media content creator with relatively cheap recording equipment, a myriad of entertainment options saturating the current media market, and consumers being more than ready to dispose of traditional media and embrace the new ones, the world seems to be moving on fine. What else is there worth commemorating still?

The incident that happened on 28th of May 2001 will always be known as the 528 Press Injury by the Chinese community. Business tycoon Quek Leng Chan announced his decision to sell 72.35% of Nanyang Press Holdings’ equities to MCA’s investment arm, Huaren Holdings, despite facing protests from the Chinese community and dissenting writers who went on strike. 5 years later, said equities changed into the hands of Tan Sri Tiong Hiew King, which made him the largest owner of Nanyang Press Holdings. Tiong had then successfully monopolized the Chinese press industry as he owned 4 out of the 6 main Chinese newspapers in West Malaysia. In 2008, Tiong merged Sin Chew Media Corporation, Nanyang Press Holdings, and Ming Pao Enterprise (Hong Kong) to form Media Chinese International, which went on to be dual-listed on Hong Kong and Malaysia’s exchanges.

The Nanyang takeover crisis was the epitome of Malaysia’s freedom of speech and the authoritarian state-controlled press. Special permission is required to operate in the Malaysian media industry, and so the state and its governing party will be at an advantageous position to acquire such licensing, directly allowing them control over the media in all major languages. Most of the well-known media groups are either state or political party owned, while the other private media groups are operated by cronies friendly with those in power. As Malaysia lacked anti-monopoly laws against the concentration of media ownership, it is a winner-takes-all situation for the state’s political cronies. Armed with huge capitals and shielded by their fellow politicians, these cronies acquire monopoly over the media sector and willingly offer their services to clamp down on press freedom, so as to maintain a conducive media environment that favours the state and its political and capitalist cronies.

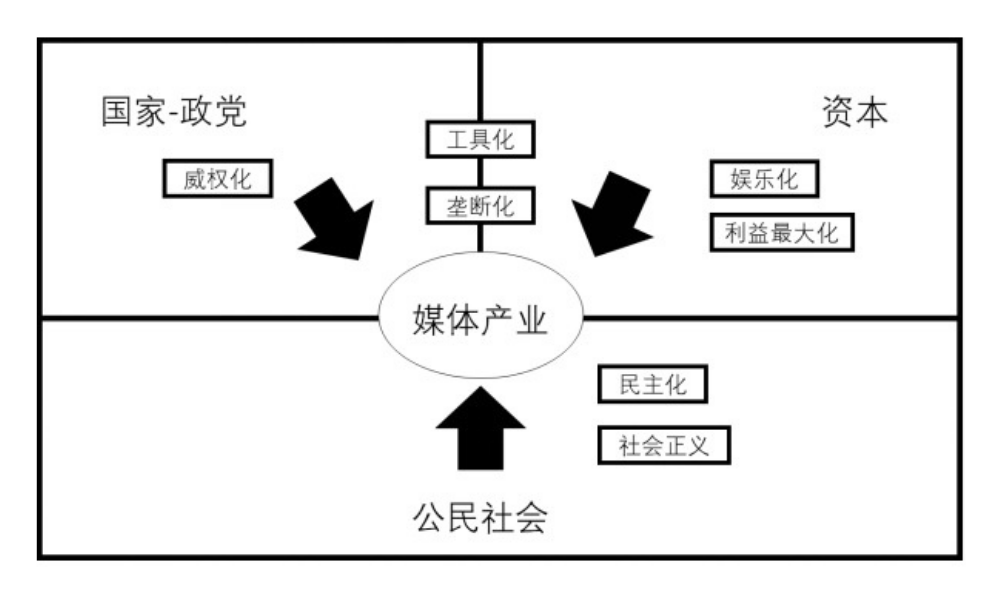

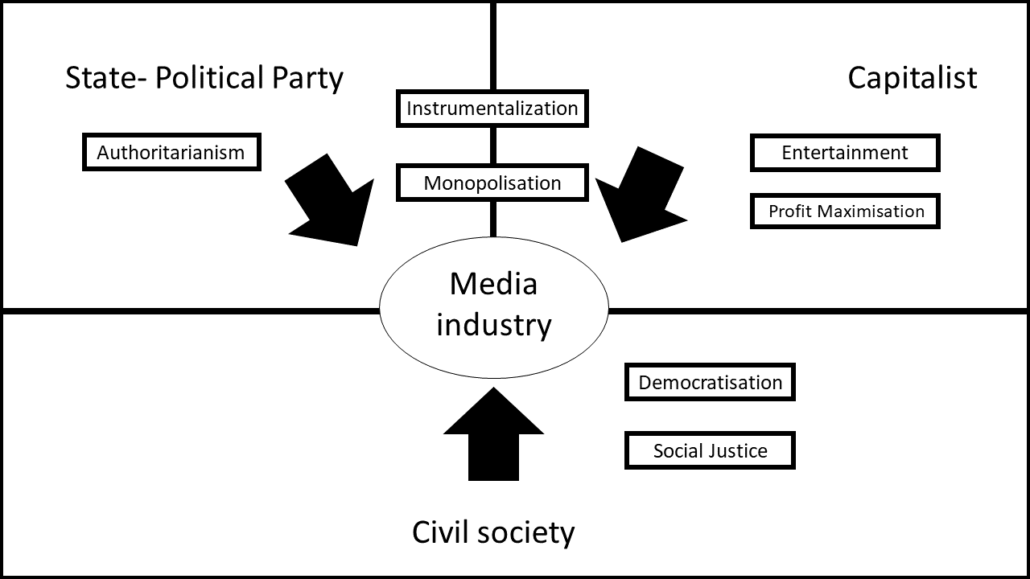

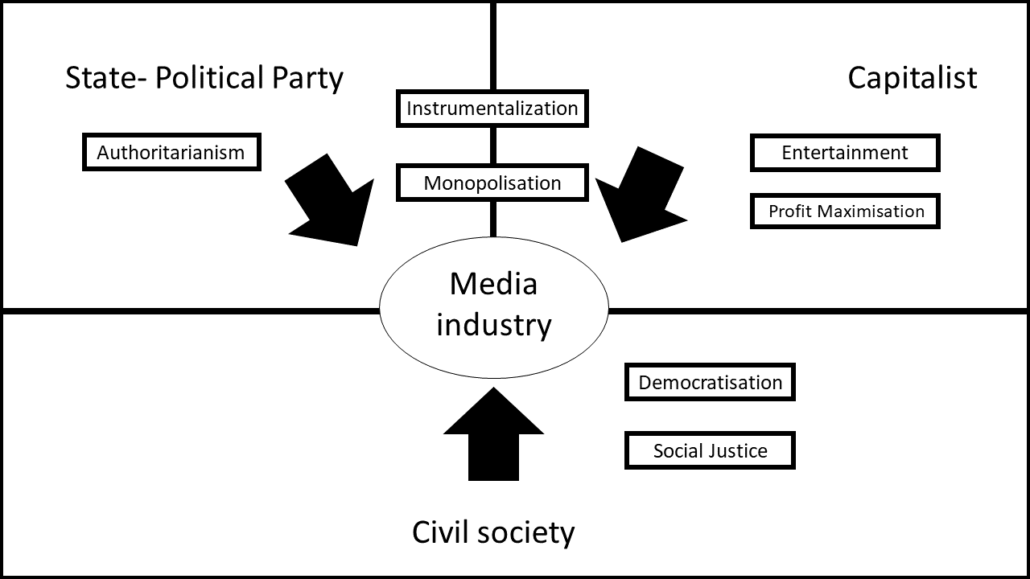

When the people’s interest was dulled by the traditional press and electronic media, the internet served up fresh alternatives for their information consumption. Self-media groups with limited capitals are able to survive under the income brought in by consistent traffic when social media such as blogs, YouTube, and Facebook came into bloom. Not long after, the internet was also swamped with viral entertainment content produced by online celebrity. The capitalists naturally pounced on such opportunities to take up their share of profit from the online market. Apart from uploading their current media content onto social media, they also engage celebrity to be their product spokesperson. Under this partnership arrangement, both online celebrity and capitalists are maximizing their profits and mutually benefitting each other. As of now, the online media strives hard to compete for watch time, trying their very best to convert the attention traffic towards generating capital for themselves. The following chart illustrates the current situation faced by our media industry.

Resisting the information bombardment from the authoritarian state and capitalism

Meanwhile, our civil society sees no further than short-term demands and mobilisation. The people’s participation in demanding for free press and media is best witnessed through incidents such as Malaysiakini’s contempt of court case and Utusan Malaysia’s large-scale retrenchment. As much as we wish that our media could move towards democratisation and advance social justice, the long-term development and management of alternative media groups are faced with challenges from draconian media laws, funding constraints, and a lack of mass appeal. On top of that, Malaysians lack education in media literacy to deal with the information bombardment from our authoritarian state and capitalism. Instead, we are succumbed to the mind-numbing scrolling over posts and short clips on social media, where the exaggerated acts of vulgar pranks and the empty talks of politicians were put on loop to evoke a conditioned yet involuntary laugh that prompts us to scroll on even further.

Right now, Malaysia is undergoing a difficult phase of transition from the authoritarian rule to democratic governance. Our freedom of speech is policed by the authoritarian power, and on the other hand we are gasping for air under a media environment that intends to amuse us to death. Our event “Reflecting on Malaysia’s Media Freedom: 20 Years After the Malicious Acquisition of Nanyang Press” is an attempt to elevate the public dialogue, revisit our past wounds in media censorship, and to contemplate the future of Malaysia’s media industry.

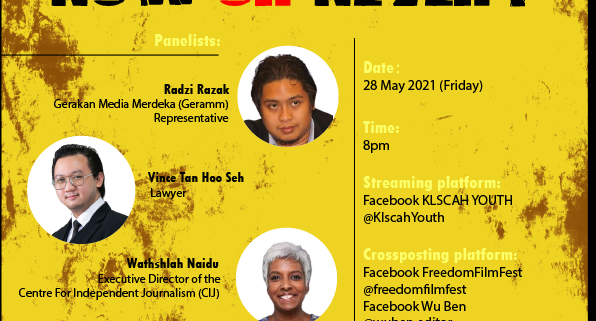

Held in collaboration with KLSCAH Youth, Freedom Film Network and WuBen Film Magazine, this event consists of an online forum and two documentary screenings. On the day of 28th of May, we have “Media Council, Now or Never?”, an online forum that discusses the roles that the media council, media laws, and media practitioners play in reshaping the industry’s landscape. The forum will be moderated by Soo Hoo Yi Yi, assistant secretary of KLSCAH, and our line of panelists are Radzi Razak from Geramm, Vincent Tan Hoo Seh, a law practitioner, and Wathshlah Naidu, the executive director of the CIJ.

Our memories and our forgetfulness on power

For the online documentary screenings, we are first featuring the local-made Nasir Jani Melawan Lembaga Puaka. This documentary narrates what Nasir Jani and the new generation of filmmakers have always been wrestling with — The Film Censorship Board of Malaysia (LPF). Zikri Rahman, the co-producer of this film, revealed that the word play on “Lembaga” could be understood as both the institution of the film censorship system and also a spectre of the authoritarian power.

As content creators, both film makers and news producers have suffered under the authoritarian rule. They would have to first censor their own works in the making, trying hard to gauge the kinds of content that might not get past the authorities. The fear that their works will be banned hangs over their heads long past the production process. Three filmmakers, Nasir Jani, Lau Kek Huat, and Anna Har are invited to talk about the problems on local film censorship, and the session will be moderated by Daniyal Kadir.

The second screening features “Documentary of Appledaily”, a Taiwanese documentary that tells the story of Apple Daily and the Anti-Media Monopoly Campaign. The owner of Apple Daily, Next Digital, was stationed in Taiwan in 2003. This incident marked the official start of an era where businessmen took over the roles of intellectuals in the news production industry. Next Digital led the featuring of sensational news and gossip in the industry and later joined in the competition against Want Want China Times Media Group to acquiring monopoly over the media industry. With the rise of new media came the cease of Apple Daily’s print publication. This was coincidentally a mirror of what happened also to our local Malay Mail and Oriental Daily, where all these press outlets moved all their operations online. The theme of our post-screening discussion focuses on the state and capitalists’ control over media, and will be moderated by Oung Kang Wei, the organising committee member of this event. Our board of panelists consists of Kevin H.J. Lee, director of the documentary, Low Chia Ming, Malaysiakini’s seasoned reporter, and Cheah Khui Chen, Lyceum Society’s president.

Two decades have passed since the malicious acquisition of Nanyang Press. What will we collectively remember still in the ten years to come? Milan Kundera once said, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” The quote went on to be the face for many resistance movements, but what significance does it have over this incident? To us, what more important is to remember that we will always the prey waiting to be devoured by the authoritarian state and its cronies who will do anything to get to where the profit lies. When the winner continues to take all, the Malaysian media reform will hardly be ever within our reach. Democracy would not come easy, and it is only through the constant struggles and resistance of the people could we have a chance of exiting the shadows of authoritarianism and wake up from amusing ourselves to death.

Reference

- 庄迪澎/报殇十四年,就只剩下钱了!链接:http://mediamalaysia.net/archives/4491

- 傅向红、李永杰/越界与想象:反思民办媒体教育与社会变迁(上)。链接:https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/77408

- 傅向红、李永杰/越界与想象:反思民办媒体教育与社会变迁(下)。链接:https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/77469

- 【自由电影节/02】娓娓生活泪 泪光闪烁尽记电影中。链接:https://www.sinchew.com.my/content/content_2382653.html